Why bigger is better when it comes to time trial chainrings

It isn’t just a case of riders wanting faster gears. There are real performance gains to be had from fitting giant chainrings

Alex Hunt

Junior Tech Writer

© GCN

Ahead of the stage 2 time trial in this year’s UAE Tour, riders were spotted with chainrings that were bigger than we’d ever seen before.

The biggest that we encountered belonged to Ineos Grenadiers’ Tobias Foss who was running a massive 68-tooth chainring, but right across the peloton, riders are using much bigger chainrings than we're used to seeing. Even on the hilly TT that propelled Remco Evenepoel into the leader's jersey at the recent Volta ao Algarve, the world champion was using a 62-tooth front ring.

Although TTs are getting faster, there is far more to this new trend than just bigger gears. Here’s why riders are opting for larger chainrings.

It’s not about faster gear ratios

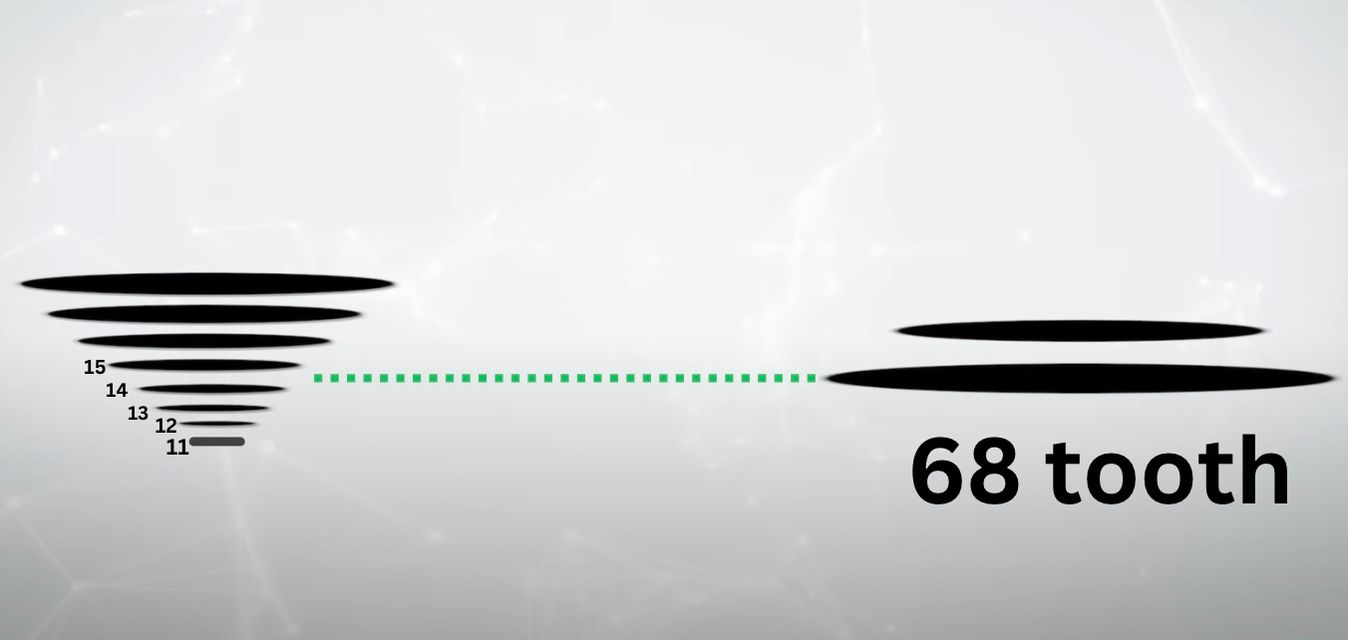

Contrary to popular belief, bigger chainrings are not being used to give riders bigger gears. If a rider was able to push a 68x11 gear at 100rpm, they would be touching nearly 80kph, which simply isn’t possible.

© GCN

Big chainrings are not directly for faster gears

For context, time trials are often won with average speeds of around 55kph, with a swing of a few kph either way depending on the course. Even for rolling courses, having gears that you could theoretically push to 100kph doesn’t seem to make any sense.

In this deep dive into this new trend, we are going to work around a simulated TT speed of 55kph and we will work with a nominal cadence of 95rpm to keep all calculations comparable, albeit open to a bit of interpretation.

It is all about drivetrain efficiency

In the past, time trial bikes have used road gearing. There were a few exceptions to this, such as Tony Martin and Fabian Cancellara who were both known to use 58-tooth chainrings which, at the time, were considered monstrously large. For modern road bikes, regular road chainrings are in the 52 to 56-tooth range.

The problem with using 53 or even 55-tooth rings is that, to pedal at 55kph, you need to use one of the smallest sprockets on the cassette. A 55-tooth chainring, for example, would need to be paired with a 13-tooth sprocket to achieve the target speed. On a standard Dura-Ace cassette, this would be the third sprocket from the bottom.

Although this leaves two extra gears in the bank for when the road points downhill or for a sprint to the finish, it means that for most of the TT, the chainline of the bike is far from optimal.

© GCN

Keeping the straightest line between the chainring and cassette can have a measurable benefit to drivetrain efficiency

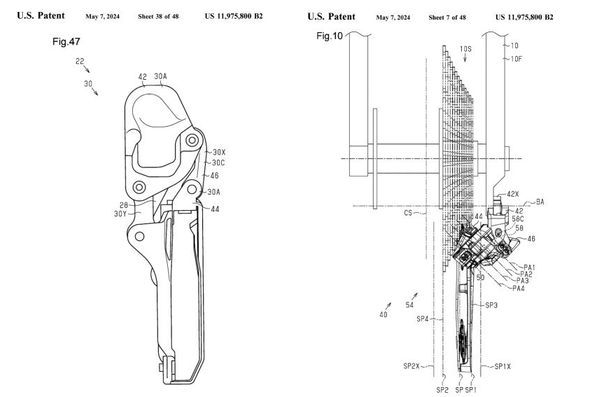

The chainline of a bike is characterised as the path the chain takes from the chainring to the cassette. For a perfect chainline, the chain should travel in a perfectly straight line between the cog at the front and the back. The further away from this optimal configuration you get, the more issues you run into regarding drivetrain efficiency losses.

When the chain has to travel to the extremities of the cassette, it has to deflect significantly from the perfect chain line. This deflection introduces frictional losses to the system that need to be overcome. An unoptimised chain line can cause around an additional 5 watts of resistance, something not to be sniffed at in the detail-oriented science of time trialling.

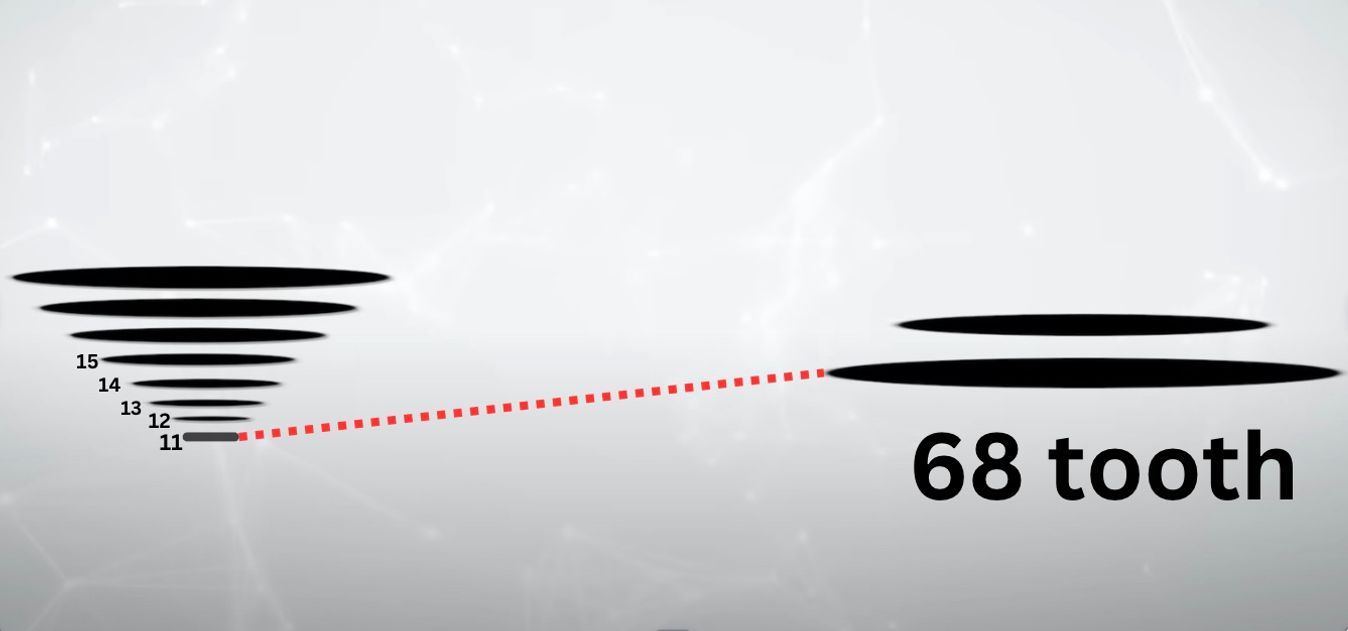

This is why we are seeing riders starting to use mammoth chainrings as it allows them to sit in effectively the same gear as a 55 x 13, but with a far straighter chain line. If we take Tobias Foss’s 68-tooth chainring, for him to ride at 55kph at a cadence of 95rpm, it would need to be paired with a 16-tooth rear sprocket. As it so happens, a 16-tooth rear sprocket on a Dura-Ace cassette is the sixth sprocket from the bottom. When the offset of the front chainring is accounted for, this puts the chain line as close to straight as possible.

© GCN

Deviating away from the perfect chain line causes the chain to deflect which introduces additional resistance than needs to be overcome

It is likely that we are going to see more riders working out what gear they are going to need for their average speed on a time trial course, then fitting a chainring that allows them to stay in that middle cog as much as possible.

Evenepoel demonstrated this at the recent Volta ao Algarve time trial with a 62-tooth ring. This left him a low enough bottom gear to haul himself over the course undulations whilst ensuring that for the majority of the course, he was able to keep a straight chainline.

Is it just about chainline?

For the most part, the chainline advantage is the number one reason riders are running bigger chainrings, but it is not the only benefit to be had. Running bigger chainrings, and therefore larger sprockets, also increases the efficiency of the system as the chain has to take a less aggressive path around the profile of the sprocket. The more that the links of the chain have to bend, once again, the more frictional losses that are introduced into the system. With a larger sprocket, the chain can take a smoother path around the cassette and derailleur, once again saving crucial watts.

What does this mean for one-by drivetrains in road races?

As soon as you stray from those middle cogs on the cassette, efficiency is a bit of a sticking point for one-by drivetrains. With one chainring responsible for accommodating the full complement of sprockets at the back, there is the potential for greater overall efficiency losses than with a traditional two-by configuration when you stray into the upper and lower reaches of the cassette.

In time trials, the range of speeds that the riders travel at is fairly small, so riders rarely have to use the full spread of gears. In all but the flattest road races, the pace varies much more, and it's inevitable that riders will spend time in all gears across the cassette at some point throughout a race. This means that a one-by drivetrain will suffer greater losses than a two-by set-up, which can more appropriately balance the chain line and prevent ‘cross chaining’.

© GCN

One by drivetrains in TTs can be optimised however for road stages it is far harder to achieve

Chainrings are the latest area of pro bike tech to receive the marginal gains treatment, with mathmatical optimisation producing measurable savings that could make the difference between winning and losing. Keep your eyes peeled this season to see if this trend takes hold across the peloton and 62-tooth chainrings and above become the norm.

Have you experimented with large chainrings or do you use a one-by setup on your road bike? Let us know in the comments.