The Dutch turned the Netherlands into a bicycle utopia. Here’s how we can do the same in other countries

Chris Bruntlett, author of Building the Cycling City: The Dutch Blueprint, tells us how the rest of the world can learn from the Netherlands

James Howell-Jones

Junior Writer

Photo by Sabina Fratila on Unsplash

Cycling in the Netherlands is safe, relaxing and efficient

Places where more people cycle and fewer people drive are better for everyone, cyclist or not. Just take a look at a typical city in the Netherlands, the number one bicycling nation in the world. The streets are quiet, save for conversations caught in the breeze, the occasional ring of a bicycle bell and the odd car rumbling slowly over cobblestones. People sit outside cafes in tree-shaded plazas. The air is clean and safe to breathe. Pedestrians stray between the sidewalk and the road without concern – there is no Dutch word for ‘jaywalker’. Dutch towns are living, breathing places, not car-choked traffic jams.

The question is, how did the Netherlands end up so different, and how can we make our towns and cities more like theirs? To find out, we spoke to Chris Bruntlett, International Ambassador for the Dutch Cycling Embassy and author of Building the Cycling City: The Dutch Blueprint.

As Bruntlett explains, the Dutch success story is not an accident of geography. The safe, pleasant streets of the Netherlands are the product of bold campaigning, brave politics and intentional urban planning. Understand the process, and the ‘Dutch blueprint’ is something we can export to cities all over the world. In fact, look around the world and you’ll see that, here and there, it’s already under construction.

Read more: Cycling in the USA – The case of Richmond, Virginia

How do Dutch cities work?

In towns and cities across the Netherlands, most people do not naturally reach for the car keys when they need to pop to the shops, take their kids to school or go to work. In a large-scale 2019 survey by the European Commission, an incredible 62% of Netherlands residents said that on a typical day, their main mode of transportation is, or is used in combination with, a bicycle or scooter (ie. a push scooter or electric scooter, not a moped). Meanwhile in the UK, just 3% of the UK population said the same.

People still drive in the Netherlands: 47% of trips in the country are taken by car, if you count both the driver and passengers. But with so many people opting for other modes of transport, especially for inner-city journeys, the streets of the Netherlands feel completely different to most cities in the world, as Bruntlett explains.

“Less road maintenance, reduced health care costs, less air and noise pollution, improved safety: everybody in the city benefits from getting more people cycling, whether you get on a bicycle or not, in terms of your pocketbook, in terms of your taxes, in terms of your quality of life,” he says.

So how do Dutch cities work? Quite simply, they make driving inconvenient and make cycling and public transport quick, easy and enjoyable.

“Within the city, they make it really attractive to ride a bicycle," explains Bruntlett. "It's through really high quality, smooth, red asphalt separated cycle paths, where possible; nice wide spaces where you can ride side by side with a friend and have a conversation.”

The network of cycling paths is complete, without gaps or pinch points. Transferring between cycling and public transport is easy too, with secure parking at railway stations and ample room for bikes on trains.

Meanwhile, and perhaps most importantly, the towns and cities are designed to make driving a car slow and long-winded. Driving routes within Dutch cities, Bruntlett explains, “are a little bit indirect, a little bit inconvenient, recirculating the traffic to perimeter ring roads so that it’s not filtering through residential and commercial parts of the city.”

Add to that limited parking, low speed limits and restrictions for high-emission vehicles, and you get cities that are a pain to drive around, and a joy to cycle through. With that in place, people choose the mode of transport that offers the lowest resistance.

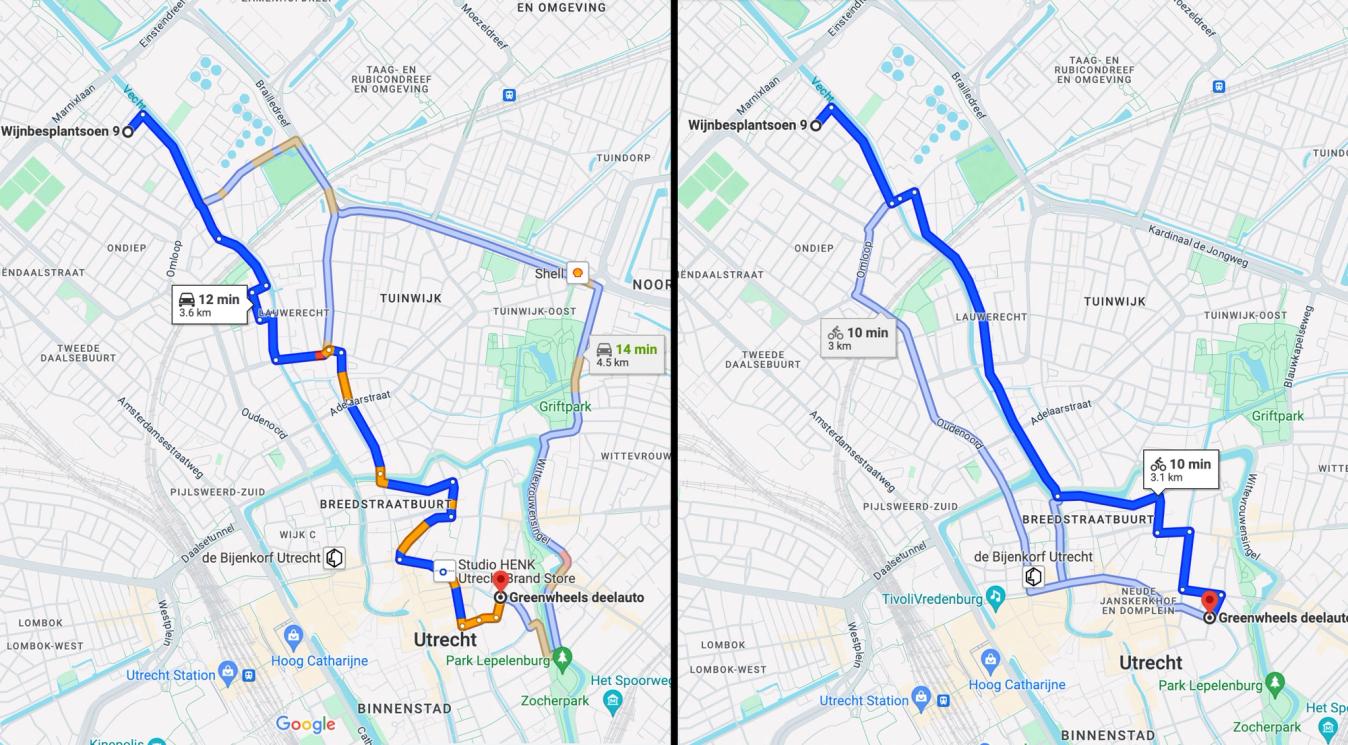

© Google Maps 2024

Quicker by bike: a typical journey into Utrecht, Netherlands

How did the Netherlands end up so different?

You might assume that the Netherlands has just always been a bicycling nation. In fact, it was only in the 1970s that it started to shift away from car-centred design.

After the second world war, the Netherlands was building its cities around the automobile, just like everywhere else, as Bruntlett explains:

“It was widening streets, demolishing buildings, even filling in some of its historic canals to make way for automobile traffic. That continues unchecked for a couple of decades, and it’s not until the mid 1970s that this tipping point happens.

“The residents of the Netherlands have had enough of the rising car traffic. They can see the lack of safety. They can see the lack of space, particularly for their children, and they mobilise politically. They take to the streets to protest the rise of the car in their neighbourhoods and in their communities.”

Dutch National Archive

Stop de Kindermoord protest in 1973

Most of those protests went under the ‘Stop de Kindemoord’ (stop the child killings) banner; over 3,000 people were killed on the roads in the Netherlands in 1972, around 25% of which were children. Appalled, Dutch residents blocked streets and occupied collision black spots to force politicians to change things.

“This is accelerated by an oil crisis in 1973 that implemented ‘car-free Sundays’. The price of gasoline skyrocketed, the sale of bicycles doubled, and it created a perfect storm.”

Dutch National Archive

People enjoy the empty streets on car-free Sunday

“It caused both the residents to demand more from their elected officials, but also the politicians themselves to recognise that the current trajectory they were taking towards the car-dependent society was unsustainable.”

Dutch residents were not campaigning for bicycles. They were campaigning for quiet, unpolluted and safe streets. Streets that everyone, from the youngest children to the most elderly adults, would feel safe using.

“The bicycle was just there,” says Bruntlett. “It emerged as, not the one-and-only tool that people use here, but as the perfect tool for trips of, let's say, 3 to 5 kilometres within the city. Not just to your office, but to the shops, restaurants, public transportation facilities, schools; the trips you take in your neighbourhood.”

In fact, Bruntlett says that it’s only in recent years that Dutch authorities have really built around the need for bicycles.

“It’s really accelerated in recent years. All this development, all this momentum has led to networks that are really high quality, really complete. They don't have a lot of gaps or pinch points, to the point that in most cities in the Netherlands, the bicycle is the predominant mode of transportation. And in some places like in Utrecht, in Groningen, in Amsterdam, bikes make up more than 50 to 60% of the traffic in the city.”

What’s stopping other countries from ‘going Dutch’?

Sadly, in most other countries, we’re more set in our ways than the Dutch were in the 1970s.

“The privilege that the Netherlands had was that it made the decision 50 years ago to not go down that path of car dependency,” Bruntlett concedes. “As each year passes, it becomes more and more difficult to unravel that vicious circle of car dependency, and it's not going to be without short term pain for long term gain.”

Physically, our cities have become sprawling, grid-patterned expanses of business districts, shopping malls and suburbs. Culturally, we’ve been conditioned to believe that roads should be dangerous places; that we should ‘Stop. Look. Listen. Live.' So can we bring about our own transport revolution elsewhere?

“You may not reach 50 or 60 percent of all journeys on a bicycle in your city, but you could probably reach 10 to 20 percent just by building out a network; just by making it safer and more comfortable for people to cycle,” says Bruntlett.

He believes that simply by redesigning urban spaces, we can shift behaviour and get people out of cars, and onto bicycles.

“Research has shown that 60 to 70 percent of the population are this ‘interested but concerned’ segment. They would ride a bike or walk or take public transport more, they're just concerned about the discomfort, the lack of safety.”

A recent wide-scale survey from the British government found that 61% of Brits would be encouraged to cycle more if the roads were safer. 48% of respondents said that safety concerns are the reason they do not ride a bike.

“They are basically a captive audience to car dependency; they drive, but only because they don't have any other choices. And those are the people we should be talking to; those should be the people that we're designing for.”

Politically, policy that inhibits the freedom of drivers will always provoke noise and outrage. Bruntlett says that this vocal minority does not represent the public’s views.

“Street space and how we allocate street space is incredibly political, and we all feel a sense of ownership over how space on the street is allocated. When we start talking about unravelling that vicious circle of car dependency, when we start talking about deprioritising a mode of transportation that has been privileged for so many years, certain people get very angry, and I always stress: this is not representative of the larger community.”

Photo by Matt Seymour on Unsplash

A Low Traffic Neighbourhood in London, UK

Bruntlett uses Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTN), a contentious UK policy in which some residential streets are blocked to through-traffic, to explain:

“We've seen that particularly in the UK with the Low Traffic Neighbourhoods; very small segments of the population have fought against them. Some have even resorted to vandalism.

“When it comes to actually talking to the people that live in those low traffic neighbourhoods, they remain immensely popular, quietly popular, and the politicians that supported them do very well at the ballot box.”

Indeed, the latest polling found that 58% of Londoners support the introduction of LTNs, whilst only 17% opposed blocking residential streets to rat-running motorists. It’s the same story with the highly controversial ULEZ, a fine for high-pollution vehicles, which 58% of Londoners say they support, and just 24% say they oppose.

If we want to deploy the Dutch blueprint, then, our challenge is to make that quiet majority heard by our politicians.

“We have to somehow give a voice to the voiceless. We have to somehow quantify that latent demand, that quiet majority that exists in our communities, and we have to help politicians understand that this isn't just the right thing to do. It's also, quietly, the popular thing to do.

“Politicians don't listen to the quiet people. They listen to the loud, noisy, disruptive, intensive minority that will prevent any change from happening in their community.”

A change is going to come

To make our cities more Dutch, we need to make cycling safer, and we need to make it harder to drive around towns and cities. It might feel like a constriction of liberty to the noisy minority, but most will appreciate safer, quieter, cleaner streets.

Thankfully, at this point, we do not need to speak only in hypotheticals. Bruntlett names several success stories, many of which have taken consultation from the Dutch Cycling Embassy that Bruntlett represents. Among them is the city of Manila, Philippines, where in 2020, the government built almost 500km of bike infrastructure in less than a year. In a post-construction survey, 64.5% of respondents said they had been cycling or using light mobility vehicles more since the paths were put in place.

Elsewhere, there are signs of change. In February 2022, the European Parliament passed a historic resolution calling for a European cycling strategy to double the amount of kilometres cycled in Europe. In Paris, there is a bold €290 million plan in the works to turn the French capital into a completely cyclable city by 2026. And last summer, in Milan, Italy, there were echoes of the historic Stop de Kindermoord protests when people took to the streets demanding safer conditions for cyclists and pedestrians.

“When I start talking about the Netherlands,” concludes Bruntlett, “you always hear the same bad faith arguments and it is, ‘well, we're not the Netherlands because we're not flat’ or ‘we're not dense and compact’, or ‘we don't have beautiful weather that the Netherlands has.'”

The success of cycling in cities around the world, from the freezing streets of Copenhagen to the expansive districts of Austin, Texas, shows that it is not geography that keeps people in cars and stops people from embracing greener, healthier and quieter modes of transport. In reality, it comes down to two things, both of which are within the control of city planners: how safe is it to cycle, and how convenient is it to drive? Balance those two things properly, and people will change their behaviours. Not because they have to, but because they want to. The surveys and polls make clear that most people want change: they want cities that are safe, clean and quiet – cities that follow the Dutch blueprint.